Developing a farming system that ties together principles of sustainability and productivity is complex. Organic farmers must consider how the various components of their system—rotations, pest and weed management, and soil health—will maintain productivity and profitability. If you’re already using some of the practices discussed in previous sections, you’ve already started thinking about your farm as a system, and organic may be closer than you think. While the fundamental concepts and practices of organic agriculture are universal, the way you achieve certification will vary based on the kind of system you’re working with.

This section lays out basic transition strategies for livestock, field crop and horticultural systems. It also includes broad approaches to transitioning your land as well as additional resources you might find useful.

Livestock Systems

Traditionally, livestock have played an important role in integrated farming operations and fit well in organic farming systems. For example, livestock:

- Feed on forages and grasses, which are essential components of the annual crop rotations and perennial cropping systems used by organic farmers because they prevent soil erosion and build organic matter

- Provide manure, an important organic fertilizer

- Can graze land that is considered marginal or not suitable for commodity crops

- Can be effective weed control agents (in particular, sheep, goats and chickens)

- Are raised year round and can generate income throughout the year instead of just at harvest time

The initial investment of time and finances to transition an animal system is high because you’ll likely have new input, infrastructure and labor costs while still receiving conventional prices, so careful financial planning, risk analysis and, oftentimes, a gradual transition that spreads out costs over time, are essential to a successful transition. The higher prices you often get after certification should make up for the large investment, but during your transition planning period you should confirm contract pricing and/or market opportunities for your organic products to ensure this will be the case. For example, a 2016 analysis by the USDA of small-scale dairies (organic and conventional, up to 199 head) found that organic dairies had higher costs than conventional ones but much higher returns. Also, the only segment that broke even that year was organic dairies with herd sizes of 100–199 head.

Organic rules require that livestock health and natural behavior be accommodated year round. One application of this rule is that livestock must have daily access to fresh air, sunlight and the outdoors, and that ruminants must have access to pasture. So if you’re already providing outdoor access and grazing your ruminant livestock, the transition to organic will be less complicated than if you operate a confinement system. In the 1990s, many beef producers in Nebraska entered the organic market with ease because they were able to adapt existing pasture-based systems they’d perfected over the years, according to the Center for Rural Affairs. In addition, dairy farmers who use pasture as a major feed source and who are balancing milk production output with herd health practices that don’t require routine use of antibiotics and hormones also find it easier to transition.

Keep in mind that even if you’re using pasture and providing outdoor access, you must follow other rules as you convert to organic. For example, buffer areas on pastures may be required if there are contamination risks, such as spray drift, from adjacent land use. Additionally, organic regulations require that pastures be managed in a way that protects natural resources, including water quality, which may mean fencing livestock out of streams and other natural water sources.

Although the land to produce organic grain, hay and pastures must be managed according to organic standards for three years, dairy cows only need to be managed organically for one year before they can be certified for organic milk production. As a cash-flow strategy, some operators transitioning to organic sell off the milkers and keep the young stock for this transition period. Heifers eat very little grain, so it isn’t too expensive to feed them organically during the transition year. In some instances, a farmer will choose to sell their conventional herd and buy an organic herd once their land is ready for certification. Organic slaughter stock (swine, beef animals, lambs, goats, etc.) must be managed organically from their last third of gestation. Organic poultry must be managed organically from their second day of life.

Poultry farmers who have adopted outdoor, minimal confinement systems also may have an easier transition to an organic system. The small but growing practice of raising broilers, layers and turkeys in pasture-based systems lends itself to organic certification because it meets two of the requirements of the national rule for organic meat: outdoor access for livestock and elimination of antibiotics in feed. Most alternative poultry producers already avoid antibiotics, as birds not crowded together in confinement systems experience fewer infections. Producers still need to watch for diseases and weather-related stress. To prevent disease and stress, many organic farmers move the birds frequently, allowing pathogens to die off when their food source is removed, and they clean pens and brooders regularly between flocks.

Because outdoor systems don’t require elaborate or expensive housing, organic livestock systems may cost less than confinement systems and are thus a viable option for beginning farmers or those who have trouble raising capital. Poultry, for example, can be raised on pasture using inexpensive, easy-to-build structures.

Animal Health

One of the biggest challenges when transitioning livestock is finding alternative approaches to animal health, since hormones and antibiotics are prohibited. In organic systems, the focus on animal health is almost entirely preventive. In fact, many organic farmers find that the incidence of diseases typical in a confinement system is generally reduced by pasturing the animals, providing better nutrition and following preventive care practices. For example, because animals aren’t standing on cement, they tend to have fewer foot and leg problems, while the fresh air reduces respiratory problems. Organic dairy farmers also see reduced incidence of mastitis due to improved immune systems and overall health, different bedding practices (including time on pasture) and lower milk productivity demand.

Focusing on animal nutrition through high quality feed and good soils also goes a long way toward reducing stress, illness and the need to treat animals for medical problems. Hubert Karreman, a dairy veterinarian, organic veterinary medicine consultant and dairy farmer in Saxapahaw, N.C., agrees that the incidence of many diseases is lower in organic and grazed herds. “But,” he adds, “just because you’re using organic management does not mean you won’t have health problems.” He sees more pasture bloat, hoof punctures and abscesses in grazed animals, but he also believes that preventive strategies such as probiotics (immune system builders), homeopathy and botanical medicines can be used very successfully to manage and treat organic herds.

Transition Strategies: Livestock Systems

- Research different organic livestock systems, including the animal species that fit best with your climate, farm system and management skills.

- Take stock of what you already have, including buildings, fences, pasture and cropland, labor, expertise and breed genetics. What changes will you need to make?

- Create a business plan that includes market research to confirm you’ll have a market for organic livestock products. Focus on lower-cost changes, waiting until you have more experience to add larger investments and changes.

- Be sure you have a reliable source of organic feed, and make sure you have backup sources in case of an emergency. Be planning at least three months out to allow adequate time for emergencies and other feed source failures, as organic feeds are not as readily available as conventional sources.

- Develop a recordkeeping system that allows you to track each animal or flock from birth to slaughter (or sale), all feed produced or purchased, and all health treatments.

- Discontinue prohibited practices. This may involve culling animals susceptible to health problems such as lice or parasites. Since you’ll be giving up conventional veterinary medicine you’ll also have to figure out how to improve conditions to foster good health among the herd or flock. Alert your veterinarian about your transition plans before you move ahead.

- Prolonged periods of stress will have a negative effect on livestock health and will make organic management more challenging, so look for ways to reduce stress in housing and handling practices. For example, poor ventilation, a lack of dry places to rest, overcrowding and handling that upsets animals are typical sources of stress.

- In dairy systems, expect cull rates to go up at first, because the older cows may have a hard time fitting into the new system.

- Anticipate decreased milk production in dairy production systems if your ratio of forage to grain increases in the livestock rations. Stay focused on the bottom line rather than on production numbers.

- Consider using operating loans to bridge the gap while you’re buying organic inputs but selling into conventional markets. In your business plan, include projections for when you think you can repay these loans given your anticipated costs, production levels and prices received during the transition and after certification.

- When possible, partner with other transitioning and organic growers to share equipment, storage and other resources.

—Partially adapted from the Rodale Institute’s Transition to Organic Course

Field Crops

Research shows that organic field crops can be more profitable than a non-organic corn–soybean rotation on a per acre basis. The 40-year Farming Systems Trial at the Rodale Institute, the longest running side-by-side comparison of organic and conventional grain in the United States, has produced some stunning results. In drought years, organic fields can produce up to 40% higher yields than non-organic systems. Organic systems also earn 3–6 times higher profit, use 45% less energy and release 40% fewer carbon emissions. An economic analysis of another long-term comparison study, the Variable Input Crop Management Systems Trial in Lamberton, Minn., found that an organic system using a four-year rotation of corn–soybeans–oats/alfalfa–alfalfa produced a net return that was 88% higher than a conventional system using a two year corn–soybean rotation (Delate 2015).

Prices for organic grains, like conventional grains, are variable, which often increases risk and may cause some farmers considering the transition to organic to hesitate. But, “it’s not clear that transition costs are or have to be high,” says Jeff Schahczenski, an agricultural and natural resource economist with ATTRA. “It’s more about learning how to get better yields and managing costs well.” Three other barriers listed by the Organic Trade Association’s U.S. Organic Grains Report include:

- Uncertainty that the organic prices at the end of the transition period will be as high as when starting the transition

- Lack of easy access to markets for lower-value crops used in rotations to control weeds and build soil health

- Lack of technical assistance and resources

A SARE-funded survey (LNC17-397) of field crop growers in Indiana found additional constraints. For one, many growers rent land, and this, along with tight margins, makes them reluctant to switch to long-term investments like organic. Some growers were also worried about negative social pressure.

Yet, many farmers have successfully transitioned to organic field crops by using a variety of strategies and carefully assessing their land and markets. Common transition strategies used by farmers range from a complete “cold turkey” approach to gradual ones that transition some plots of land before others. Others may take a split approach, where the farm is permanently split between organic and conventional land. (See the section “Select the Pace That Works for You.”) A gradual or split approach might work better if you think the labor-intensive nature of organic farming will be hard to manage initially, or as a way to manage the risk associated with the learning curve of trying something that is considerably different than what you’re used to. Networking with local organic growers more experienced than yourself is critical to the success of any transition approach because you can gain both encouragement and important insights about the best production and marketing practices.

For Rory Beyer and his family, who farm dairy, beef steers, corn, small grains and alfalfa, the “a-ha” moment came after a year of volatile milk prices and high feed costs. “I had been watching our [certified organic] neighbors. … They were feeding their own grain, producing less milk and making more money,” Beyer says. “So I started looking at what it cost us on a per cow basis to produce feed, buy feed and deliver it to our animals.” After running the numbers, the family decided to transition to organic. One successful strategy they used was to negotiate a decrease in rent on 130 acres they rented during the transition period, in exchange for higher rent after certification. The Beyers developed a four-year rotation of hay–corn with a winter cover crop of rye or tillage radish–corn–alfalfa seeded with a small grain. Like many other mixed operations, they also transitioned their land ahead of the animals, allowing them to have certified grain and forages ready to feed their own herd when the animals transitioned. This allowed them to avoid paying higher organic prices for feed while they were still getting conventional milk prices.

Transition Strategies: Field Crops

- The biggest factors contributing to yield decline during the transition are available nitrogen and weed competition. Focus on controlling problem weeds and building soil health with cover crops and other practices very early in, or even before beginning, the transition. Improving soil fertility takes time, so try to avoid beginning the transition with a heavy nitrogen-feeding crop such as corn. Ideally, begin instead with a perennial forage of nitrogen-fixing legumes such as alfalfa. Beginning with soybeans may present challenges with initial weed management and crop quality.

- Seek out current and historical pricing via USDA-NASS, which has been compiling bi-weekly organic cash (spot market) price data for corn, soybeans, wheat and hay-alfalfa since 2006. Look up 10-year price histories for organic commodities to help you determine how to price your grain. A good resource for a discussion of organic pricing is the ATTRA publication Understanding Organic Pricing and Costs of Production.

- Consider subscribing to Mercaris, a private company that publishes a market survey of organic and non-GMO grain prices that you can use to track current prices and view historical prices. (This is a recommendation by the authors and does not constitute an endorsement by SARE or the USDA. Exclusion of other businesses does not imply a negative endorsement.)

- Look for companies that may offer a little more for alternate labels or for transition production practices while you’re in the transition. For example, some companies (mostly grain and dairy) may offer non-GMO and “transition premiums,” usually at $1–$2 above conventional prices. Check Mercaris for listings of non-GMO pricing.

- Use the Organic Grain Resource and Information Network (OGRAIN) to improve your organic row crop and small grain operation. OGRAIN, located in the Midwest, provides extensive information on everything from farming practices such as weed control and termination of cover crops; marketing, including buyers and brokers; grain storage; and organic transition and certification. OGRAIN also includes OGRAIN Compass, a planning tool with a spreadsheet and tutorial booklet to help you understand the financial implications, at both the crop and whole-farm level, of pursuing organic grain production.

- Talk to other organic farmers and attend Extension and farmer-focused events to learn from experienced growers. Explore and consider joining existing organic marketing co-ops, such as OFARM, that can provide expert market advice as well as assistance at a minimal cost to you.

Horticultural Systems

Organic fruits, vegetables and herbs comprise approximately 12% of total U.S. produce sales. Growers with well-developed markets can expect high returns; depending on the product, organic prices currently range from 20–200% over conventional prices.

When planning your transition, use your Organic System Plan from the get-go “as an opportunity to design offensive and defensive strategies,” says Danielle Treadwell, associate professor and state Extension specialist of organic and sustainable vegetable production at the University of Florida. Defensive strategies are those that you plan against known risks, while offensive strategies are to prepare you for threats that might arise. For example, defensive strategies can include variety selection, grafting and crop rotation, all of which offer protection against pests you expect will arrive. Offensive strategies might include soil building practices and diversifying your crops. It takes time, adds Treadwell, but “well-planned offensive strategies always pay off in the end.”

Offensive strategies may also include planning ahead financially and considering what tools you’ll need, perhaps even investing in tools such as a cultivator ahead of time to help defray loss of income during the transition years. Another example of a good defensive strategy would be to adapt your marketing strategies in response to how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed your sales.

Because timing is so critical in horticultural systems, you’ll want to spend time mastering the practices organic farmers use to tackle weeds, one of the biggest problems in organic horticultural systems. Specifically, this means getting a handle on your use of cover crops, pest scouting and, most importantly, cultivation, throughout the rotation calendar.

Transitioning to organic horticulture systems also requires you to become a good observer of the whole farm, and that you learn to think about your system at a landscape level. For example, how can you adapt your hedgerows to provide habitat for beneficial insects? What’s the best way to balance cultivation for weed control with the need to build soil organic matter through reduced tillage? Without the usual chemical arsenal of rescue solutions, you’ll have to be far more reliant on the landscape-level ecology of your system to prevent problems.

Smaller systems within the farm that can be micromanaged and that offer protected cultivation, such as high tunnels, greenhouses or plasticulture, can be smart places to start a transition, as the protection will allow you to lower your risk.

“Protected cultivation is more powerful in organic. It can provide a larger return faster in transition,” says Anu Rangarajan, the director of the Cornell Small Farms Program. For example, in greenhouses, and in high tunnels to a lesser extent, you can screen the space against insects and manage moisture. Of course, if you’re producing organic seedlings or crops in high tunnels or in other greenhouses, you must follow organic regulations in your management of those structures.

Additionally, plasticulture can be used as a targeted micro-management area to help you reduce two of the biggest challenges in transition: weeds and nutrients. Plastic mulch will give you a jump on weeds by providing crops with a more steady supply of nutrients. While plasticulture is acceptable according to NOP regulations and can be helpful during the transition, many experts and farmers discourage its ongoing use because the huge amount of landfill waste it generates goes against the principles of organic agriculture. There are no biodegradable mulches currently on the market that meet NOP standards, although this may change in the future.

Moving to drip irrigation can make a big difference in disease and weed control. For example, a SARE-funded research project (SW01-057) involving large-scale vegetable growers in California transitioning to organic found that adopting dripline for irrigation and delivery of soluble organic fertilizers not only conserved water and cut costs, but also reduced the incidence of weeds and diseases by keeping the surrounding soil dry.

Along with cultivation and nutrient supply, finding crop varieties less susceptible to disease and insect pests will go a long way toward a successful transition. It’s “your first line of defense,” says Rangarajan. And, she adds, don’t just settle for the varieties you’ve been using, but think about how to move beyond them to find ones that will adapt well to your farm and systems, and that have a high level of disease resistance. When selecting varieties of crops, consider traits related to disease resistance or an ability to compete with weeds, as well as other desirable traits like yield or flavor.

Successful organic horticulture farms also make use of grafted rootstock to manage pests, as grafted crops are more resistant to soil-borne diseases and tend to yield higher than non-grafted ones. Because grafted plants cost more, you may want to reserve their use for high-value crops. They’re commonly used in high tunnels or greenhouses.

Transplants are also useful in organic systems. Transplants can minimize damage from certain insect pests, help with weed control and also alleviate timing constraints brought on by use of cover crops and uncertain weather. For example, transplants allow you to push back your planting date to allow cover crops to grow longer, or allow you to plant your crops into existing mulch and/or and give plants a head start over weeds. (If using seedlings that you didn’t start, during your transition be sure these transplants were grown following organic standards; after your transition is complete, seedlings that are sourced from off the farm must be certified organic.)

Last but not least, prepare for labor needs to increase both on and off the field. You’ll be spending more time in the field as you plant and terminate cover crops, use mechanical or hand cultivation, and scout for pests. Also, be prepared to spend more time locating, purchasing and having approved inputs shipped, particularly if the products you need aren’t produced in your state.

Transition Strategies: Fruit and Vegetable Crops

- Practice the management skills you’ll need during transition, such as cultivation and scouting, before you start transitioning your farm, so as to be skilled at them when you’re ready to transition.

- Prepare for the increased amount of time it takes for planning, doing paperwork and working in the field.

- Evaluate a wide range of new crops and be willing to let go of certain high-value crops in order to diversify, which will help lower risk.

- Experiment with the wide range of tools available to you to control weeds, such as solarization, flame weeding and drip irrigation.

- Transition on fields that have the best soils and that are relatively free of weeds.

- Study crops and varieties in your area to determine those that are least susceptible to disease during transition. For example, in the Northeast, squash and potatoes have a high susceptibility to disease and aren’t considered good transition crops, whereas tomatoes, which are hardier and have disease-resistant varieties, generally perform better and are recommended as good transition crops.

- Modify your landscape to control pests and to invite beneficial insects and pollinators by planting flowering cover crops and wildflowers at field edges. This creates habitat for natural enemies and positively impacts crop production. In the field, use row covers and crop rotations to disrupt insect and disease cycles.

- Don’t forget sanitation for disease control. Clean all tools, boxes, implements, stakes and any other materials that can vector diseases, weed seeds or insect larvae.

General Transition Strategies

Regardless of your farming system, there are some ways you can ease, and possibly speed up, your transition to organic certification. These include finding the approach that works best for you, taking advantage of existing educational and financial resources, and looking for land on your farm that might be eligible for a quicker transition because of how you’re currently managing it.

Select the Pace That Works for You

There’s no one strategy for deciding how much acreage to transition. Many successful organic farmers have ventured into organic a little at a time, which makes the switch more manageable and gives them time, at low financial risk, to evaluate what’s working in different areas like fertility or pest management. Others find that they can successfully transition large amounts all at once. Consider which of these approaches works best for you.

- Transition one parcel at a time. Start with limited acres, with the intention of eventually transitioning all land (and livestock, if applicable). Your pace can be dictated by availability of finances and labor, and to minimize risk. Experiment with a portion of the farm rather than with the entire acreage. Transitioning one parcel at a time also helps minimize the economic losses you may face during transition.

- Gradual transition. Withdraw one class of prohibited products at a time, or start by reducing your use of fertilizers and herbicides, and monitoring pests for threshold levels. Preliminary results from a North Carolina study investigating the impact of withdrawing classes of inputs show that there were no yield differences between conventional, transitional and organic soybeans for the first year of the transition. This approach will delay how quickly land can be certified—three years of complete withdrawal from prohibited synthetic chemicals is required—and may impact your profitability. However, if you market directly to consumers you may be able to take advantage of your transitional status to fetch a moderate premium.

- Split transition. Manage some land conventionally and some land organically as a long-term strategy. This is often combined with the “gradual” transition strategy, but the intent is to simultaneously maintain both organic and conventional land. Keep in mind that all equipment, crops and machinery must be separated between the operations, and everything you use for the organic side must be maintained according to regulations.

- Cold turkey. Originally this wasn’t considered a wise strategy because it was thought that it took 3–5 years of organic production before soil and field quality began providing desirable yields, but there’s more information now on how you may be able to minimize yield declines associated with the transition. For example, research shows that if you use crops that don’t have high nitrogen requirements, or if you select varieties that can fix their own nitrogen, you may see favorable yields sooner. Moreover, legume crops such as soybeans are easy to cultivate and can perform well even with all chemical inputs withdrawn.

- Immediate transition. Certify livestock and land with minimal or no transition period. Immediate certification is often an option for land under conservation agreements that hasn’t been actively farmed for three or more years, but you’d still need to provide records showing that no prohibited substances have been used over the most recent three years. (See the following sections, “Coordinate with NRCS Programs” and “Hidden Acres.”)

Using Alternative Labels During the Transition

You can’t begin capturing organic price premiums during transition because you aren’t allowed to label anything organic, even though you’ve already started the organic farming process. However, by using third-party labels, you can inform consumers that your product is not conventionally grown and thus possibly get a small price increase. If you direct market at the farmers’ market or to restaurants, you can take the time, while in transition, to explain your practices. Some growers even use these third-party labels first and then eventually transition to organic.

Most of these labels have far less recordkeeping and lower costs than organic certification. They address a range of farming practices such as grass-fed and humane treatment for livestock, non-GMO for crops and fair trade for social justice, making them appropriate for a wide range of farming systems in transition. (A primer for consumers is at www.farmaid.org/food-labels-explained.)

Because there are many labels out there, all with their own rules you’ll need to follow and varying degrees of influence in the marketplace, it’s critical to do your research and consult with local marketing specialists before you proceed with one. It’s also important to remember that organic is the only certification managed by federal law, meaning it has more oversight and regulation behind it than third-party labels. These regulations may give some consumers more assurance about the quality and consistency of products bearing the organic seal.

Coordinate with NRCS Programs

EQIP initiatives for organic transition. Many conservation practices encouraged by NRCS—soil health, erosion control, nutrient management, crop rotation, biodiversity, buffers, and habitat for pollinators, beneficial insects and wildlife—align closely with organic practices. Recognizing this overlap, NRCS has developed programs under its Environmental Quality Incentives Program Organic Initiative (EQIP-OI) to help organic and transitional growers.

For transitioning growers specifically, NRCS has designed the Conservation Action Plan 138 (CAP 138), which focuses on developing a conservation plan that protects resources while also helping build the foundation for your Organic System Plan (OSP), which is required by certification agencies. In some cases, the CAP 138 will be identical to your OSP, and the technical service provider will even help you fill it out. CAP 138 also provides funding to implement parts of the plan and provides you with free technical assistance. A technical service provider doing your CAP 138 planning can even help you design your farming practices for transition.

NRCS funds other plans under CAP 138, including nutrient management and pollinator habitat management. It can also help you develop management calendars and job sheets for implementing conservation practices.

NRCS can also help ruminant operations design a grazing plan for their land. This can be used to verify compliance with the organic requirements for the ruminants’ feed rations from pasture as well as to complement the OSP.

Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). This program helps farmers and ranchers who have already implemented some conservation practices on their land expand on their efforts. The whole-farm production approach to conservation that CSP encourages fits well with organic systems. When you enroll in CSP you work with a local NRCS conservation planner to identify a variety of conservation practices that you could implement to address your specific natural resource concerns while meeting your farm management goals. CSP provides financial support for the practices you choose to implement in a five-year contract with the option to renew for an additional five years. Examples of eligible practices include:

- Grazing management to improve wildlife habitat

- Extending filter strips to reduce excess sediment, nutrients and chemicals in surface water

- Planting cover crops to improve soil health

- Planting range grasses to reduce erosion and develop wildlife habitat

Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) land. If you have CRP land and can document it hasn’t received prohibited inputs for three years, it may qualify for immediate certification. However, be fully aware of why the acreage was originally put into CRP. There may have been a production issue that prompted this action, including susceptibility to erosion, wetness or soil never meant to be cropped in the first place. If your CRP land was placed there because of low productivity, you’ll want to ease into organic management with a legume, such as field peas, which can provide its own nitrogen, as it will take time to build healthy soil on the land. Also consider planting a cover crop in the fall to boost soil activity for a spring crop. A SARE-funded study on Iowa CRP land (LNC99-160) showed that there was virtually no economic loss when transitioning using soybeans. By the third year, the economic returns in the certified organic soybeans were 180% above conventional.

As of 2021, the USDA is considering a proposed rule change that would discourage the practice of turning native ecosystems into organic farmland by requiring a 10-year waiting period to gain organic certification. Under this proposal, CRP land would likely be affected if it has regained important characteristics of a native ecosystem. Be sure to consult with an organic certifier to learn about current regulations—and consider your own land stewardship goals—before you consider bringing CRP land into crop production, particularly if your CRP land is considered highly erodible or is best used as a buffer strip. On marginal land, livestock grazing may be the best option for organic production, as it can be done without degrading the land’s condition as a native ecosystem.

Hidden Acres

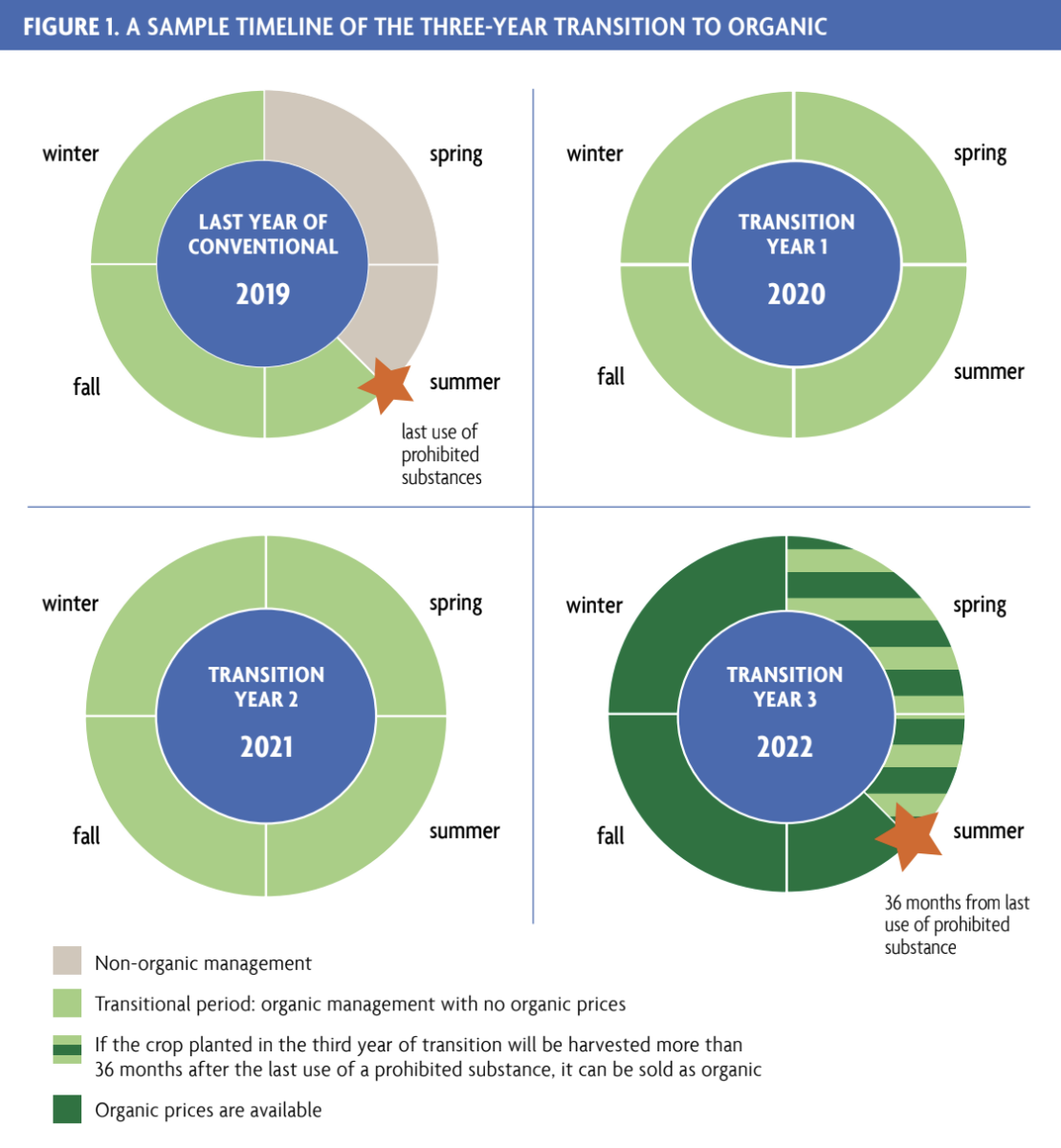

One of the biggest challenges in transitioning is the three-year period (36 months) known as the “dead zone” of transition. This is the period when you may have a three-year yield drop, increased costs and no access to organic prices, making them very difficult years. By searching your farm for “hidden acres,” you may be able to partially transition some of your land in less than three years. Keep in mind that if the date for crop harvest occurs 36 months and one day after the last prohibited practice on the field, that crop can be certified organic and receive organic pricing, thus shortening the “dead zone” in many instances (Figure 1).

You can find these hidden acres in:

- Alfalfa. If your alfalfa has been grown for three years using non-GMO seed and without prohibited substances as listed by the NOP, you can transition this land directly into organic. The land will be in excellent condition for organic production since alfalfa improves soil structure and suppresses weeds.

- Fallow land. If you have any acreage that hasn’t been planted and hasn’t had any herbicides or prohibited substances applied, you may subtract those fallow years from the three-year countdown. Of course, you’ll need to do soil testing to evaluate fertility and, following that, decide how to transition crops into this land.

- Winter wheat. If you’ve grown winter wheat with no prohibited substances, this can also reduce your time to transition. You can also consider moving toward transition by growing winter wheat using only approved NOP materials. Either of these approaches will cut the transition time.

- Grazed fields. Any fields/pastures that have been grazed and have not received any prohibited materials, such as GMO seeds, fertilizers or pesticides, may be able to transition into organic immediately. You’ll want to evaluate soil health carefully and make a plan to increase soil health, particularly if you placed those fields into grazing because of low productivity in the first place.

- Cover-cropped land. If you start with a warm season cover crop in the spring on land that has received no prohibited inputs since the fall, you can plant a cash crop into this land after a second year of cover cropping. In order to qualify as organic, cash crops only require three years from the time of application of the last prohibited substance to the time of harvest, not to the time of planting. This means that the cash crop can be planted after two cover crop cycles, so long as it is harvested at least 36 months after the last prohibited substances were applied.

If you want to use any of these strategies to cut down your transition time, be sure to keep careful records of everything you’ve done, from the seeds you’ve planted to all materials applied. All certifiers will require you to verify everything you’ve used in fields that you want to transition early. Search online for the National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances maintained by the NOP to understand which substances you need to avoid. Also, you should get assurance from your certifier as early as you can that the practice is allowable, and include it in your OSP. Interpretation of rules and regulations may vary slightly among certifiers, so having documentation can prevent disappointment or confusion later. If the land hasn’t been under your management for the transition period, a signed affidavit from the previous landowner or land manager is required as verification that no prohibited materials were applied during the transition period.

—Adapted from Hidden Organic Acres? 6 Scenarios For a Faster Transition (AgriSecure)

Don’t Start From Scratch: Use Existing Resources

In the early days of organic certification, farmers had to rely on each other and a scarce supply of data. The knowledge base is considerably larger today and continues to grow; for example, the 2018 Farm Bill allocated $395 million over the next 10 years to organic research through the USDA’s Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative. Likewise, the number of people who can work with you as consultants has grown significantly since the early days of organic. Tips for learning include:

- Many state Extension offices have organic specialists and knowledgeable county agents. In addition, many organic agriculture associations exist at the state, regional and national levels. Reach out to local organizations to find specialists and farmers you can begin networking with.

- Visit eOrganic.org, which offers an expansive collection of information on organic agriculture–including dairy, grain, fruit, vegetable and poultry production–collaboratively developed by university researchers and Extension specialists from around the country. The site includes articles, videos, webinars, courses and an “ask an expert” tool.

- Look for field days, farm tours, conferences, winter workshops and on-farm trials that focus on organic and provide an opportunity for networking with others who are either interested in transitioning or are experienced organic farmers.